what is seed diversity about?

Intensive agriculture and biodiversity erosion

The development of intensive agriculture has led, since the 1950s, in the consolidation of agricultural plots, the expansion of fields cultivated in monocultures over huge areas, the mechanisation and division of labour, as well as the increased use of chemical inputs.

Less well known, the promotion of a few so-called "high-yielding" plant varieties resulting from modern agronomic selection techniques caused a fashion for perfectly standardised plant products to appear on the market.

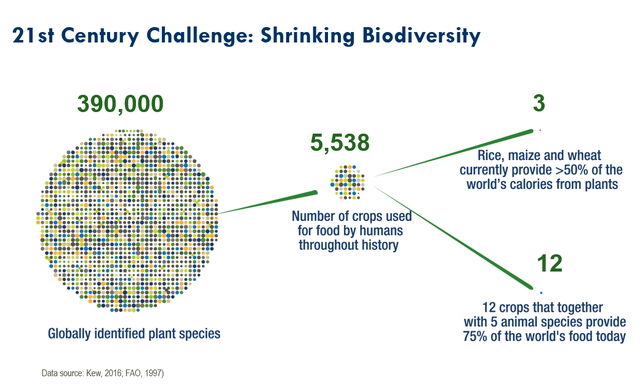

This standardisation of agricultural production, which has spread to most of the world, has inevitably resulted in a significant loss of cultivated biodiversity. Although this phenomenon is relatively unknown to the general public, it is very evident in the various agricultural markets around the world. Everywhere, the attentive consumer will notice the distressing uniformity of the plant products offered for sale. Thousands of traditional varieties have been commercially replaced by one or two representatives of the species, leading to the gradual disappearance of genetic resources capable of sustaining an abundant and necessary agricultural diversity.

Since the 1990s, numerous reports on this phenomenon have been published by European or international institutions. The most important of these are the United Nations for Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reports "on the state of the world's plant genetic resources", published in 1998 and 2010. The first one states that "many of the plant genetic resources that may be essential for the future development of agriculture and for food security are now under threat. Country reports indicate that recent loss of diversity has been significant and that the process of 'erosion' is continuing. In this respect, the irreversible loss of genes is of great concern, as this is the fundamental functional unit of heredity and the primary source of variation in plant appearance, traits and behaviour." (State of the World's Plant Genetic Resources Report, FAO, 1998, p.13).

In 2004, the FAO carried out a quantitative assessment of this process. It concluded that since 1900, more than 75% of agricultural biodiversity has been lost worldwide. In farmers' fields, the situation is even more worrying, as more than 90% of traditional varieties are no longer cultivated.

The responsibility of restrictive legislation favouring standardisation

The erosion of cultivated biodiversity is partly linked to the implementation, since the 1950s, of very restrictive legislation concerning the rules for marketing plant varieties for agriculture, market gardening and gardening. In the European Union, only varieties listed in the official catalogue of cultivated species and plants may be marketed. Through the obstacles it poses to the registration of varieties, it has acted as a very narrow funnel for biodiversity, contributing to a drastic reduction in the commercial offer and thus in the diversity of plants grown by farmers.

The biggest losers in the impoverishment of cultivated diversity and the consequent simplification of the commercial supply of plants and plant products are undoubtedly the end consumers. They have lost out on all fronts: in terms of choice and freedom of what they can grow and eat, in terms of taste, nutritional quality of their diets and the level of health that can be expected from them, as well as culturally, because traditional varieties were associated with specific knowledge, customs and culinary traditions which are consequently being forgotten. In supermarkets, it is often only one unidentified variety of each plant species that is offered for sale, and this variety has usually been selected for its productive yields, resistance to transport and shelf life. Not for its taste or nutritional qualities.

Organic farming is currently no exception to the rule, as the varieties used in this crop rotation are the same as those used in chemical farming. As the official catalogue imposes its standardisation criteria without distinguishing between farming methods, there has been no variety selection developed for the specific needs of organic farming. As a result, organic farming has been deprived of the necessary genetic tool to optimise its performance and attract its customers. However, taste is primarily a function of the genetic make-up of the seeds. The quality of the soil, the mildness of the climate and the cultivation practices only play a secondary role.

A recent legal breakthrough could make it possible to change this situation though. Indeed, the European Regulation on Organic Production which was adopted in 2018 and entered into force in January 2022, included significant legislative potential for increasing European crop biodiversity, by allowing for the marketing of two new categories of organic seeds exempted from the costly testing and mandatory registration in official catalogues:

- The organic heterogeneous material (OHM) of plants not expressing the formerly mandatory criteria of distinctness, uniformity and stability;

- New so called organic varieties adapted to the specific needs of organic agriculture.

The impact of these phenomena on human health

Since the 1940s, it has been widely accepted that there is an inverse relationship between productive yields and the concentration of minerals in plants. This is known as the "dilution effect".

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a number of British and American studies attempted to clarify this relationship by introducing an additional variable: the one of varieties grown. These studies made comparisons between historical nutritional data for certain fruits and vegetables and more recent comparable data.

The first British study of this kind, published in 1997, reported a significant decrease between 1930 and 1980 in the calcium, magnesium, copper and sodium content of a group of 20 vegetables and in the magnesium, iron, copper and potassium content of a group of 20 fruits. The average decrease ranged from 17 to 80%, with copper showing the greatest decrease in the vegetable group. Only phosphorus showed no significant difference over the 50-year period. The water content had increased significantly and the dry matter, especially in fruits, showed a significant decrease. As for proteins and vitamins, one of the American studies, carried out on a panel of 43 vegetables, showed an average decline of 6% for proteins and a reduction of 15 to 38% for three of the five vitamins studied.

To address criticisms of the unreliability of historical data as a basis for comparison, other methods have more recently been implemented. Different varieties from different eras have been grown side by side under the same conditions of soil, fertilisation, irrigation, pathogen control, climate, harvesting and sampling, in order to determine the exact role played by the genetics of the varieties tested. These studies involved broccoli, wheat and maize. They confirmed the findings of previous studies and revealed a real "genetic dilution effect" for the "high-yielding" varieties.

These Anglo-Saxon studies are most likely valid for the whole of Europe, because its agriculture, copied from the American model, implements the same practices and uses the same seeds.

In 70 years, the yields of our agricultural products have increased considerably. They have doubled or even tripled depending on the species. At the same time, in industrialised countries, men and women have increased their daily calorie consumption. Yet more than 3 billion people, almost half of the world's population, suffer from nutritional deficiencies in one or more specific nutrients. The public health consequences are severe, ranging from anaemia in the widespread case of iron deficiency, to partial or total blindness for those without access to adequate sources of vitamin A, to the well-known epidemic of obesity and diabetes that is currently plaguing the industrialised world.

Plant Breeders' Rights against food security

With regard to seeds and their evolution over the last 70 years, another problem must be noted: the fact that most of the seeds listed in the official catalogues are not reproducible, either because they are locked by agronomic selection methods that make them 'sterile' seeds that cannot be used commercially (F1 hybrids), or because they are legally protected by intellectual property rights (Plant Breeders' Rights - PBR). Farmers, but also amateur gardeners, cannot reproduce them from one year to the next, and are therefore forced to buy them each year, or must pay an annual fee to breeders, holders of Plant Breeders' Rights. These techniques for appropriating living organisms have gradually enabled a small handful of multinational companies (Limagrain, Bayer-Monsanto, BASF, Syngenta, etc.) to largely control the world seed market.

This presents a major risk, on a global scale, to the sovereignty of peoples to feed themselves and to ensure their food security. Taking away people's control over the main input for food production, as well as depriving them of this ancestral human capacity to produce the most suitable seeds for each territory, under evolving and adaptive conditions, including climate change, greatly increases the possibility of food crises.

For all these reasons, it is essential that European legislation on seed marketing accompanies the transition of agriculture towards more sustainability, resilience and sovereignty. Solutions in this direction already exist. They are supported by actors who embrace agriculture in all its complexity, advocate short circuits and know how to innovate while relying on practices that predate the industrial model. For a long time pushed into illegality by the effect of unsuitable legislation, they have never ceased to exist and continue to develop, driven by the desire to protect and enrich a genetic heritage dating back nearly 10,000 years of agricultural history. They must now be massively supported, relayed and multiplied, so that cultivated biodiversity ceases to be the alternative and once again becomes the basis of everyone's diet.

All the photographs on this website were taken by professional photographers and are protected by intellectual property rights.

If you wish to reproduce them, please write to us and we will provide you with the necessary information. Thanks!