adapting agricultural practices TO climate change

Seeds, beans and lessons from the ground up

By Adèle Pautrat and Mathieu Willard

Against a backdrop of accelerating phenomena linked to global warming, the urgency to act has long since reached its peak. At this very moment, hundreds of farmers across Europe are facing extreme weather conditions and are totally powerless to cope.

Today 5 July 2023, the European Commission has tabled its proposal to reform the horizontal legislation on seed marketing. In a previous article, we expressed our concern that seed autonomy and agrobiodiversity issues are still minimised. In this one, we bring you the voice of the field. First studying the very local case of white bean production in southern France, then taking a step back to look at some key expectations expressed by our partners from different EU rural territories.

When we talk about agrobiodiversity, we talk about urgent adaptations to farming practices and genetic resources. And yet, political institutions keep on considering the development and exchange of heterogeneous seed varieties from the public domain as tolerable secondary activities which must in no way encroach on seed market share.

Even more worryingly, the arguments in favour of promoting agrobiodiversity and mitigating climate change are now being hijacked by the industry, in particular to defend so-called “new breeding techniques”.

In this context, we want to affirm our support for the many European players involved in the regeneration of cultivated biodiversity free of exclusive rights and GMOs, who have not waited for the disappearance of the obstacles to take the bull by the horns and implement ambitious projects.

So, why not draw inspiration from their experience to contribute to the development of the future European seed marketing framework?

Drawing from the leaflet on the Organic Heterogeneous Material © Francesca Casu

CASE STUDY: the white bean production sector in the Lauragais, France

On April 22, Seeds4All gathered in the agricultural high school of Castelnaudary (Aude, France) several stakeholders involved in the breeding, cultivation and promotion of legumes and more specifically beans. Among them, Axel Wurtz from BioCIVAM 11, Yuna Chiffoleau from INRAE Montpellier, Cyrielle Mazaleyrat from FILEG, Alice Bardet and Vincent Dias from QCIAF, the deputy mayor of Castelnaudary Evelyne Guilhem as well as organic farmers, seasoned gardeners and researchers.

The occasion was to discuss the implementation of a local living lab in the framework of the European project DIVINFOOD, aiming at creating a dynamic favourable to the restructuring of a sustainable and diversified local sector for the production of white beans (*Seeds4All will follow and report on this project over the coming months).

The event was also the opportunity to present the DIVINFOOD project as part of the Global bean project’s seed festival scheduled the same day, of which Seeds4All was co-organiser.

The bean gathering we organised in Castelnaudary on April 22, 2023 © Adèle Violette

A year ago we had an exchange with a member of the Global Bean project on the need to expand EU’s legume cultivation for human consumption and reduce livestock, as part of a transition to agricultural practices and diets which would contribute to climate mitigation.

In practice, however, the implementation of such a transition encounters many obstacles, linked to a lack of funding, research, infrastructure, support and varietal diversity. This is what we discussed with the associations and farmers gathered in Castelnaudary, whose testimonies we give you.

When the weight of food heritage hinders the agricultural transition

Introduced in the region in the 16th century by Catherine de Medici, the cultivation of white beans has its specific local history - and problems.

Being the main ingredient of the famous Cassoulet, it is protected by a geographical indication (GPI "Haricot lingot de Castelnaudary") since 2020. As a result “almost 100% of the local production of white bean is stamped bean for cassoulet!", regrets Evelyne Guilhem, elected official and local farmer. A situation that contributes to the rigidity of the sector, limited to a few hectares of cultivation, few actors involved and no search for varietal diversity.

In the Occitanie region, 53% of legume production is soybean, against 1% of Phaseolus beans. Nadine Micouleau, organic farmer from Lauragais, explains why she recently decided to abandon this crop which, in her opinion, offers no added value.

Uprooting, collecting, threshing and sorting beans require complicated technical skills. Most of the work has to be done by hand and access to specific machinery, such as sorting machines, is limited. Since the local CUMA doesn’t have any, Nadine and her husband were forced to send their harvest to the centre of France, and to pay the price.

On the market side, the situation is even more discouraging. While around 150,000 cans of cassoulet are produced every day in Castelnaudary, the local production of white beans does not exceed 150 tonnes per year. The production of cassoulet is therefore essentially based on imports of non-PGI white beans, even though the increase in local bean production and use is made difficult by this same PGI.

The consequences feed the vicious circle: low production is equivalent to low interest and low investment to support the development of the sector and in particular its adaptation to changing growing conditions, while the mainly cultivated ingot variety struggles to withstand repeated episodes of drought.

Structuring an alternative and sustainable white bean production sector

This is the background to the living lab for the DIVINFOOD project set up in the Lauragais region, which aims to "co-construct local plant production chains that meet consumer expectations and combat the decline in cultivated biodiversity".

As Nadine Micouleau testifies, for a local diversified farm that devotes only a small part of its land to bean production and doesn’t exceed 1 ton per year, it is very difficult to be profitable and absolutely impossible to sell across regional borders.

To ensure the future of bean production in Lauragais, taking into account climatic requirements, there is a need to encourage the emergence of a 100% local sector from seed to plate. All the players in the production and distribution chain must be mobilised, as proposed by the DIVINFOOD project that is based on a bottom-up approach involving a participatory selection protocol with amateur gardeners.

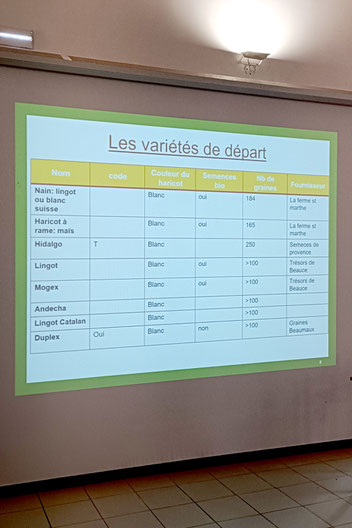

For two years, they will carry out tests in their gardens to observe and evaluate the cultivation of seven selected population varieties, in addition to the hidalgo variety which will serve as a control variety. Known as the massal selection process, this will help identify specific traits and characteristics sought by farmers, canners, cooks and final consumers (involved throughout the process via various consultation activities) before starting field trials at larger scale.

Presentation of the 7 selected varieties to the amateur gardeners © Adèle Violette

Based on the need to adapt agricultural practices while ensuring the survival of a high-potential local production chain, the DIVINFOOD living lab in the Lauragais demonstrates the importance of relying on the regeneration of agrobiodiversity through the involvement of large communities.

As we like to do, we’re now going to take a step back and try to analyse broader seed issues that the future seed law should address, based on the observations we've made in a wider range of rural areas.

BIGGER PICTURE: an overview of expectations collected on the ground

For the past two years, as part of the Seeds4All project, we’ve been conducting field visits in European territories with the aim of questioning the commitment, needs and expectations of stakeholders involved in projects that rely on agrobiodiversity and enable its development.

Our wish is to contribute to demonstrating that their work deserves to be fully supported, on the legislative and financial levels, because they have the potential to provide concrete solutions to the challenges of agrobiodiversity while guaranteeing the development of agriculture and food safety. Check all seed stories on the Seeds4All website!

Involved in commercial, militant, citizen or amateur approaches, all these players have in common to dedicate themselves to promoting rural development and food resilience, enhancing agrobiodiversity and prioritising the use of organic populations adapted to local growing conditions. In the table below, we outline what we understood from our different conversations with them.

Portraits of different partners we met across Europe © Adèle Violette

SEED AUTONOMY FOR FARMERS

Farmers require access to varieties belonging to the public domain, freely reproducible and not genetically modified. By returning the conservation and development of seeds to the hands of farmers, the risk of seed variety loss can be significantly reduced. To this end, farmers should have the freedom to reproduce and develop their varieties, engage in seed exchange and sell their seeds.

BETTER ACCESS TO ORGANIC

SEEDS AND DIVERSE VARIETIES

There is a pressing need for greater availability of organic seed in the market. Farmers, in addition to developing their own seeds, also rely on purchasing seeds. We need to better accommodate their needs as both producers and consumers, and to facilitate the development of seeds suitable for challenging specific environmental conditions. To this end, the progress made through the Organic Heterogeneous Material system (OHM) should be extended to conventional farming.

REVISED QUALITY CRITERIA

Quality criteria in pre-marketing and seed production need to go beyond yield performance and tackle objectives of environmental regeneration and climate change adaptation. To this end, other parameters should be promoted such as: tillage habits, water consumption, adaption to soil conditions, resistance to pests and disease, etc. In addition, conservation varieties as well as varieties specifically tailored for marginal environments - better suited to local contexts and specific production methods - should be better protected.

FLEXIBILITY AND

ADAPTABILITY IN FARMING

Unlike the industry, which often pursues long-term, one-dimensional projects, farmer’s seed systems and seed-saving initiatives have the ability to quickly adapt plant materials to suit specific ecosystems and climates. To this end, flexible farming practices capable of adapting to sudden and particularly disruptive exogenous events should be further recognised and supported.

SHARED BUT

PROTECTED KNOWLEDGE

Given the collective responsibility to ensure the ongoing adaptation of genetic resources and the resilience of our food systems, farmers and rural stakeholders should be helped in generating, safeguarding and sharing knowledge related to local crops. To this end, participatory breeding methods as well as initiatives allowing the exchange of knowledge and genetic resources should be further promoted and supported.

However, given the history of biopiracy around the world, rural communities and their commitment to agrobiodiversity should be protected against the appropriation of knowledge and genetic resources by public institutions or private companies seeking control and monopoly through patents or intellectual property.

CONNECTIVITY

BETWEEN PLAYERS

There is a need for greater connections and cooperation at national and regional levels between multiple stakeholders – farmers, breeders, scientists, civil society organisations, cooks, etc. To this end, modes of organisation such as cooperatives allowing risks to be shared, access to equipment and the exchange of know-how, should be further promoted and supported.

ECONOMIC

SUPPORT

We currently face several limitations to increase organic seed production: insufficient land area, inadequate marketable quantity, and a lack of entrepreneurship. According to Lebende Samen, an investment of 3 billion euros in research and development is needed to attain a 25% market share by 2035. To this end, urgent measures are required to invest in rural development, create opportunities, and improve social and economic infrastructure for rural communities.

SHORT DELIVERY CHAINS

There is a need for short delivery chains to get rid of the restrictive industrial criteria for breeding varieties and allow smaller actors to own sufficient market shares. To this end, additional means should be invested for the development of infrastructures adapted to the needs of local crops.

Another big challenge to help economic players securing local outlets is to rekindle people’s connection with local specialties, traditions, crops, etc. in a context of changing tastes and expectations of modernity. To this end, the implementation of education and awareness-raising programs/workshops from an early age should be further developed and promoted.

Need for coherent, overarching actions

The main takeaway from the table above is the need for coherent, overarching actions. Modifying seed marketing rules will not be enough. In more practical terms, the needs are larger and encompass:

1. The scope of the EU seed marketing legislation should not include the sale of seeds to amateur gardeners, any activities by seed conservation networks, the use of farm-saved seeds for farmer’s own cultivation and mass selection, the exchange of seeds between farmers or gardeners, in kind or with monetary compensation, and participatory plant breeding activities. In a broader way, there is a need to exclude from the scope any activities that focus on conserving cultivated diversity or adapting cultivars to local agro-ecological conditions. The legislation should only apply to varieties when their market value is relevant (i.e. the cost of registering it is justified).

2. Need to diverisfy quality criteria and adptability to local contexts for the varieties that will be marketed within the scope of the EU seed marketing legislation. This means that VCU testing needs to be more flexible and encompass other parameters like water consumption or adaptability to specific soils. However, appraising new quality criteria in the registration process has to be done cautiously. The EU Commission has already talked about introducing “sustainability criteria” that could be shaped to fit new GM characteristics and therefore cement a pathway towards GMO deregulation and introduction in the EU market.

3. Rules for labelling and traceability of registered or notified varieties should strengthen the need to incorporate additional details such as information about the techniques employed in developing the material, the region of production, if the seeds are F1 hybrids or GMOs, and any restrictions on its use due to patents or plant variety protections. For registered varieties, the breeding method information should be mandatory in the catalogue. Those are basic requirements to allow for better promotion of best practices.

4. Large investment packages for rural developmentshould be tabled, taking into account the priority urgency of supporting the transition to sustainable seed practices and promoting seed autonomy - development of infrastructures for seed harvesting, sorting, drying, storage; support for cooperatives and intersectoral collaboration systems; support for programs restoring genetic heritage; support for awareness and education programs; etc.. The current situation regarding the dynamic management of agrobiodiversity reflects a terrible lack of means and infrastructure on the scale of European rural territories.

5. Protection of public domain genetic resources against biopiracy. There is a need for legally framing and limiting monopolisation of the market by big corporations who can implement unfair competitive behaviours based on IPR and biopiracy. This means that a clear distinction must be made between systems that grant exclusive property rights over plant varieties and those that allow them to be placed on the market.

Left, an old variety of shallot kept in the gardens of the Lauragais / center: harvest of a typical grape variety from Aude, France, highly resistant to drought / right: seeds of a very rare variety of cucumber © Adèle Violette

Climate emergency, cultivated biodiversity and flexibility

The needs are thus legal, but also technical, financial and social. How these needs are addressed will determine the EU's ability to effectively tackle the agricultural challenges posed by climate change and biodiversity loss.

In this regard, the meetings we conducted with partners all over Europe were particularly insightful. All the locations we visited have either experienced or currently face agrarian condition changes that pose a threat to their agricultural production.

On the island of Pellworm, for example, where the rural community has to contend not only with rising sea levels, but also with the increasingly massive invasion of wild geese destroying crops. Or in the south of France, where the lack of water is felt a little earlier every year, forcing farmers to abandon certain crops.

These communities are already contemplating solutions to the problems they have experienced firsthand, and one of the key levers in the transition to practices capable of meeting new climatic requirements is to prioritise seed diversity and autonomy.

The greatest challenges of the reform process that is beginning today will therefore be to respond to the climate emergency in a strong and rigorous way, while recognising that the diversity of European contexts in terms of managing cultivated biodiversity requires flexibility and adaptability.

All the photographs on this website were taken by professional photographers and are protected by intellectual property rights.

If you wish to reproduce them, please write to us and we will provide you with the necessary information. Thanks!